5 Misconceptions Athletes From Japan Don't Understand About College Basketball Recruiting in the US (PART 2) アメリカのカレッジバスケットボールリクルーティングに関する日本のアスリートが理解していない5つの誤解(パート2)

1/26/20258 min read

Recently, Tokyo Samurai has been hosting camps in Tokyo where college coaches and scouts come to teach the game from a college coach’s perspective while also scouting for up-and-coming talent from Japan.

最近、Tokyo Samuraiは東京でキャンプを開催しており、大学のコーチやスカウトが集まり、カレッジのコーチの視点でゲームを教えるとともに、日本からの新たな才能を発掘しています。

Starting the process earlier gives players more time to navigate the challenges of international recruiting. One of the biggest hurdles for Japanese players is their English ability. Many opportunities have been lost simply because athletes could not meet the language requirements for college. Academic requirements—such as grade point average (GPA), SAT/ACT scores, and NCAA eligibility—are also essential to broaden opportunities with more colleges.

早期にプロセスを始めることで、選手たちは国際的なリクルートの課題に対処する時間を増やすことができます。日本の選手にとって最大の障害の1つは、英語力です。多くのチャンスが、選手が大学の言語要件を満たせなかったために失われてきました。学業の要件、例えばGPA(成績平均点)、SAT/ACTのスコア、NCAAの資格なども、より多くの大学と機会を広げるために不可欠です。

In Part 1, we’ve covered three critical misconceptions about the recruiting process. These insights highlight how complex and competitive it is, especially for athletes in Japan.

パート1では、リクルーティングプロセスに関する重要な誤解を3つ取り上げました。これらの見解は、特に日本のアスリートにとって、その複雑さと競争の激しさを浮き彫りにしています。

But there’s more to uncover. In Part 2, we’ll tackle two additional myths and share an essential bonus tip to help you navigate the path to college basketball success.

しかし、さらに掘り下げるべきことがあります。パート2では、さらに2つの誤解を解消し、カレッジバスケットボールの成功への道を切り開くための重要なボーナスヒントをお伝えします。

5 Misconceptions Athletes From Japan Don't Understand About College Basketball Recruiting in the US (PART 2)

アメリカのカレッジバスケットボールリクルーティングに関する日本のアスリートが理解していない5つの誤解(パート2)

Recruiting in Japan is handled differently than it is in the US. In Japan, your high school or club coach may talk with the college coach and discuss players that may fit their program. The coach may come in to see the player practice or play, or the player may come and work out with the team. The player has limited interaction with their future coach; it’s mainly handled between coaches. Everyone agrees, and they move on.

日本でのリクルーティングはアメリカとは異なります。日本では、高校やクラブチームのコーチが大学のコーチと話をし、プログラムに適した選手を議論します。コーチが選手の練習や試合を見に来ることもあれば、選手がチームの練習に参加することもあります。選手は将来のコーチとほとんどやり取りをしません; 主にコーチ同士で取り決めが行われ、そのまま進行します。

4. Coaches Will Handle My Recruiting

コーチが私のリクルーティングを担当してくれる

A mistake many players make is thinking that if they have an initial contact with a college coach, that this interaction has solidified into a bona fide offer. The recruiting process is a dance. The player interacts usually initially with the assistant coach. They build a relationship with the player. The coaches want to know what kind of person they are recruiting. As things move along, the head coach may then get involved. At this point, this is often when it becomes legitimate interest from the school. The head coach may make an offer to join the team. But the dance does not stop.

多くの選手が犯す誤解は、大学のコーチと最初に接触を持っただけで、それが正式なオファーに繋がったと考えてしまうことです。リクルーティングプロセスはダンスのようなものです。選手は最初にアシスタントコーチとやり取りをし、関係を築きます。コーチは、どんな人物をリクルートしているのかを知りたがります。事が進むにつれて、ヘッドコーチが関わることもあります。この段階で、学校からの正式な関心が示されることが多いです。ヘッドコーチは、チームに参加するようオファーを出すかもしれません。しかし、ダンスはまだ終わりません。

5. I Can Only Start the Recruiting Process in My Final Year of High School

高校最後の年になってからしかリクルート活動を始められない

In addition to recruiting challenges, players from Japan need to understand that the role they play in Japan is likely to be different when they transition to the U.S. Players who assume their play style will translate directly to the college level often find themselves frustrated. While it’s natural to expect your current position and style to carry over, the reality is that college basketball is a completely different environment. Roles are often redefined as players transition to the next level, and understanding this early can help you prepare better.

リクルート活動の課題に加えて、日本の選手たちは、日本で果たしている役割がアメリカに移行する際には異なる可能性があることを理解しなければなりません。自分のプレースタイルがそのままカレッジでも通用するだろうと考える選手は、しばしばフラストレーションを感じます。現在のポジションやスタイルがそのまま続くと期待するのは自然ですが、カレッジバスケットボールは全く異なる環境です。役割は選手が次のレベルに進む際に再定義されることが多く、これを早い段階で理解しておくことが準備を整えるために役立ちます。

Conclusion

結論

BONUS: The Role I Play Now Is Not Always the Role I’ll Play in College

ボーナス: 現在の役割がカレッジでも同じ役割になるとは限らない

Navigating the recruiting process is challenging, especially for international players facing geographic, cultural, and competitive barriers. However, with thorough preparation, persistence, and the right guidance, achieving the dream of playing college basketball in the U.S. is often within closer reach than some realize.

リクルート活動を進めることは、特に地理的、文化的、競争的な障壁に直面している国際的な選手にとっては挑戦的です。しかし、徹底的な準備、粘り強さ、適切な指導があれば、アメリカでカレッジバスケットボールをプレーするという夢は、思っているよりもずっと近くにあることが多いです。

For Japanese athletes, understanding the nuances of the recruiting process is just the beginning. Success requires more than just talent—it demands early preparation, proactive communication, and a willingness to adapt your skills to fit the demands of the next level. By taking charge of your recruiting journey and staying consistent, you can stand out in a highly competitive field.

日本の選手にとって、リクルートプロセスのニュアンスを理解することは始まりにすぎません。成功するためには、才能だけでは不十分で、早期の準備、積極的なコミュニケーション、そして次のレベルの要求に合わせてスキルを適応させる意欲が求められます。自分のリクルート活動を主導し、一貫性を保ちながら進むことで、競争の激しいフィールドで際立つことができます。

At Tokyo Samurai, we guide our players on how to navigate the recruiting process. Advice on crafting high-quality highlight reels, connecting with college coaches and participating in NCAA-certified exposure events, we provide the resources and expertise to help athletes succeed.

Tokyo Samuraiでは、選手たちがリクルート活動を進める方法を指導しています。質の高いハイライトリールの作成方法、カレッジのコーチとのつながり方、NCAA認定の露出イベントへの参加方法についてのアドバイスを提供し、選手が成功するためのリソースと専門知識を提供します。

While it’s true that some late bloomers or overlooked players have found opportunities at the last minute, waiting until your senior year can severely limit your chances. The reality is that recruiting is a multi-year process requiring proactive effort long before your final year.

遅咲きや見過ごされていた選手が最後の瞬間にチャンスをつかんだ事例もありますが、最終学年を待ってからリクルート活動を始めるのはチャンスを大きく制限してしまいます。実際のところ、リクルート活動は何年にもわたるプロセスであり、最終学年の前から積極的に取り組まなければなりません。

In the U.S., college coaches are constantly building their recruiting boards. They often start identifying potential prospects as early as middle school and actively track players during their first two or three years of high school. If you’re living in Japan, where competition and exposure are limited, this timeline becomes even more critical. Without the consistent visibility that players in the U.S. have—such as AAU circuits or national high school events—players in Japan need to start making themselves known earlier. This includes reaching out to coaches, creating highlight reels, attending summer exposure events, and working to improve their game in ways that will translate to the college level.

アメリカでは、カレッジのコーチたちは常にリクルートボードを作り続けています。彼らはしばしば中学校の段階で潜在的な選手を見つけ、最初の2〜3年間で選手を追跡します。日本に住んでいる場合、競争や露出の機会が限られているため、このタイムラインはさらに重要になります。アメリカの選手たちが持っているような、AAUサーキットや全国的な高校イベントなどの継続的な露出がないため、日本の選手たちは早くから自分を知ってもらう必要があります。これにはコーチに連絡を取ったり、ハイライトリールを作成したり、サマーイベントに参加したり、大学レベルに通用するようなプレーの改善に取り組むことが含まれます。

In the US, a majority of the recruiting process is done between the coaching staff and the player. The club, high school coach, or any other handler may make the initial contact, but a lot of the process after that involves interactions between the coaches and players through texts and phone calls.

アメリカでは、リクルーティングのプロセスの大部分がコーチングスタッフと選手との間で行われます。クラブや高校のコーチ、または他の担当者が最初の接触をすることはありますが、その後のプロセスは、コーチと選手との間でテキストや電話を通じたやり取りが多くなります。

Some players may continue to get offers from other colleges. Colleges are also looking for other recruits, in case any of the players decline their offer. Having an offer does not guarantee a spot on the team. A college can pull an offer at any point or sign other players. At the Division I and II levels, at specific times in the fall and spring, players can sign letters of intent to play for the specific school. Junior colleges also have letters of intent, while NAIA and Division III do not. A letter of intent is not a fully binding contract, as players can get out of their letter of intent, but there are necessary steps to be released from it.

一部の選手は他の大学からもオファーを受けることがあります。大学は、選手がオファーを辞退する場合に備えて他のリクルートを探しています。オファーを受けたからと言って、チームに入る保証があるわけではありません。大学はオファーをいつでも撤回したり、他の選手を契約することがあります。ディビジョンIおよびIIレベルでは、特定の秋と春の時期に、選手が特定の学校でプレーする意図書をサインすることができます。ジュニアカレッジにも意図書はありますが、NAIAおよびディビジョンIIIにはありません。意図書は完全に拘束力のある契約ではなく、選手はその意図書から解放される手続きを取ることができます。

During the recruiting process, the player needs to be proactive with contacting coaches. When there is very high interest from the college team, they will initiate a lot of contact themselves. They want to stay front of mind with the recruit. With more tepid or peripheral interest, the player needs to maintain contact with the college coaches to keep them updated on their progress. Recent game film/highlights, stats, or questions about the school/program can help maintain the connection. Recruiting is very much a two-way street; both sides need to be communicating and coming to the same conclusion that the player and the school match.

リクルーティングプロセスの間、選手はコーチに積極的に連絡を取る必要があります。大学チームから非常に強い関心がある場合、コーチは自ら多くの連絡を取ることになります。リクルートに対して自分の存在を常に意識させようとします。興味が控えめまたは周辺的な場合、選手は大学のコーチと連絡を取り続け、自分の進捗状況を更新し続ける必要があります。最近の試合映像やハイライト、スタッツ、学校やプログラムに関する質問などが関係を維持する助けになります。リクルーティングは双方向のコミュニケーションであり、両者が連絡を取り合い、選手と学校がマッチしているという結論に達する必要があります。

Getting on a coach’s radar and building relationships with programs takes time. This often happens during summer AAU events. When coaches evaluate film of athletes playing in Japan, it can be difficult to measure how good a player is relative to an American counterpart. Playing in the U.S. during the summer allows coaches to see how well you stack up against the competition. It also provides film that can be sent to coaches as proof of your ability to play at that level.

コーチの目に留まるため、そしてプログラムとの関係を築くためには時間がかかります。これがしばしばサマーのAAUイベントで起こります。コーチが日本でプレーしている選手の映像を評価する際、その選手がアメリカの対戦相手に対してどれほど優れているかを測るのは難しい場合があります。アメリカでのサマーリーグに参加することで、コーチは選手が競争相手に対してどうなのかを確認できます。これにより、そのレベルでプレーできる能力を証明する映像がコーチに送られます。

Japanese athletes may face physical mismatches and can benefit from strength training to compete with typically more aggressive American players. Starting earlier allows athletes more time to address these areas, improve their physicality, and adapt to the intensity of U.S. basketball.

日本の選手は身体的なミスマッチに直面することがあり、通常より積極的なアメリカの選手と競うために筋力トレーニングが役立ちます。早く始めることで、選手たちはこれらの部分に取り組み、身体能力を向上させ、アメリカのバスケットボールの強度に適応する時間を得ることができます。

The sooner you start, the more opportunities you’ll have to establish connections, ask questions, and find the right fit for your academic and athletic goals. Waiting until your final year to start the recruiting process can feel like trying to catch up in a race that began years ago. This is why many players opt for the prep school route, giving them an extra year to adjust, get stronger, and compete daily against more athletic competition.

早く始めるほど、コネクションを作り、質問をし、学業とスポーツの目標に合った環境を見つける機会が増えます。最終学年までリクルート活動を待つと、何年も前に始まったレースで追いつこうとするような感覚になることがあります。そのため、多くの選手は準備学校ルートを選び、もう1年の調整期間を得て、強化し、よりアスリートとして競争力のある選手と日々戦うことになります。

Think of recruiting as a marathon requiring preparation and persistence. By starting earlier, staying consistent, and keeping your goal in mind, you give yourself the best chance of making your dream of playing college basketball in the U.S. a reality.

リクルートはマラソンのようなもので、準備と粘り強さが必要です。早く始め、一貫性を保ち、目標を忘れずに続けることで、アメリカでカレッジバスケットボールをプレーするという夢を現実にするチャンスを最大限に高めることができます。

In addition to recruiting challenges, players from Japan need to understand that the role they play in Japan is likely to be different when they transition to the U.S. Players who assume their play style will translate directly to the college level often find themselves frustrated. While it’s natural to expect your current position and style to carry over, the reality is that college basketball is a completely different environment. Roles are often redefined as players transition to the next level, and understanding this early can help you prepare better.

リクルート活動の課題に加えて、日本の選手たちは、日本で果たしている役割がアメリカに移行する際には異なる可能性があることを理解しなければなりません。自分のプレースタイルがそのままカレッジでも通用するだろうと考える選手は、しばしばフラストレーションを感じます。現在のポジションやスタイルがそのまま続くと期待するのは自然ですが、カレッジバスケットボールは全く異なる環境です。役割は選手が次のレベルに進む際に再定義されることが多く、これを早い段階で理解しておくことが準備を整えるために役立ちます。

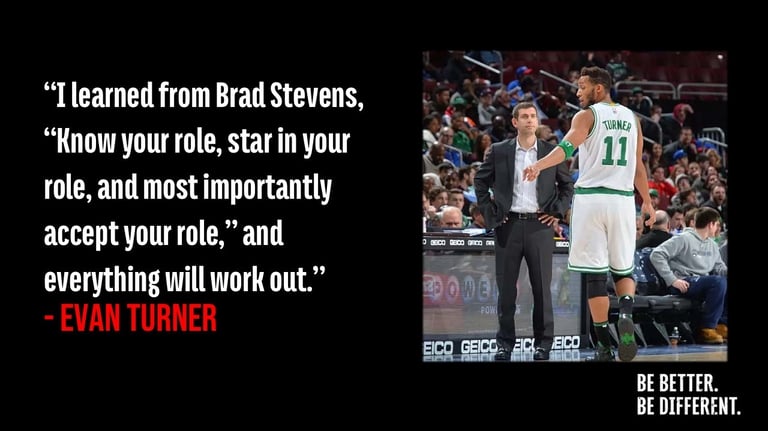

In Japan, many players are accustomed to being the go-to scorer or primary playmaker on their teams, especially if they are among the most talented players in their program. However, at the collegiate level in the U.S., every player on the roster was likely a star at their high school or club. When you arrive at college, your coach might not need another primary scorer—they might need a defensive stopper, a rebounder, or someone who excels at moving the ball and making the right plays.

日本では、多くの選手がチームの主力スコアラーやプレーメーカーとしての役割に慣れており、特にプログラム内で最も才能のある選手であれば、その役割が重要です。しかし、アメリカのカレッジレベルでは、チームの全員が高校やクラブチームでスター選手であることが多いです。カレッジに到着したとき、コーチは別の主力スコアラーを必要としているわけではないかもしれません。代わりに、ディフェンスの要、リバウンドを取る選手、ボールを動かし正しいプレーをする選手が必要かもしれません。

College basketball emphasizes specialization, and your ability to excel in a specific role will often determine your playing time. For example, if you’re a 187cm (6’2”) forward dominating in high school, you might find yourself undersized for that position at the college level, where forwards are often 2 meters (6’7”) or taller. In this case, you might need to transition to a guard role, which requires a completely different skill set—handling the ball, guarding quicker players, and shooting from the perimeter. Conversely, if you’re a guard who scores primarily by driving to the basket, you may need to develop a more consistent jump shot, as driving lanes are harder to find in college against taller, more athletic defenders.

カレッジバスケットボールでは専門性が重視されており、特定の役割で優れているかどうかがプレータイムに大きく影響します。例えば、高校で187cm(6’2”)のフォワードとして活躍していた場合、カレッジレベルではそのポジションではサイズ不足と見なされることがあるかもしれません。カレッジではフォワードの多くが2メートル(6’7”)以上であるため、この場合、ガードの役割に転向する必要が出てきます。ガードには、ボールハンドリング、より素早い選手へのディフェンス、外からのシュートなど、全く異なるスキルセットが求められます。一方で、主にドライブで得点を重ねるガードの場合、カレッジではより背が高く運動能力のあるディフェンダーに対して、ドライブのスペースが限られるため、より安定したジャンプショットを習得する必要があります。

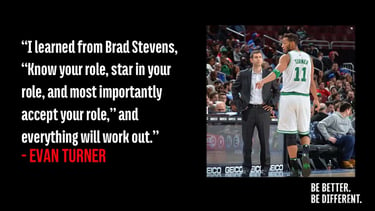

「ブラッド・スティーブンスから学びました。『自分の役割を知り、その役割で輝き、そして最も大切なのはその役割を受け入れること』。そうすれば、すべてうまくいくんです。」 — エバン・ターナー

The key takeaway is this: flexibility and adaptability are essential. If you want to succeed in college basketball, start preparing now to expand your skill set and embrace the possibility of playing a different role. Coaches value players who are willing to do what’s best for the team, even if it means stepping outside their comfort zone. The more versatile you are, the more valuable you’ll be to your future team.

重要なポイントは、柔軟性と適応力です。カレッジバスケットボールで成功するためには、今からスキルセットを広げ、異なる役割をこなす可能性を受け入れる準備をすることです。コーチはチームにとって最適なことをするために、自分の快適なゾーンを超えてでも対応する選手を評価します。より多くのスキルを持つ選手は、チームにとってより価値が高くなります。

Ultimately, the role you play now might not be the same as the role you’ll play in college—but that doesn’t mean you won’t have an opportunity to contribute. By focusing on skills like defense, rebounding, shooting efficiency, and basketball IQ, you can position yourself as a player who’s ready to make an impact, regardless of the role your college coach asks you to fill.

最終的に、現在の役割がカレッジでの役割と同じであるとは限りませんが、それでも貢献するチャンスはあります。ディフェンス、リバウンド、シュートの効率、バスケットボールIQなどのスキルに集中することで、どんな役割でもチームに貢献できる選手になることができます。

SAMURAI KAINE ROBERTS RECEIVED A SCHOLARSHIP OFFER FROM D1 STONYBROOK UNIVERSITY.

SAMURAI カイン・ロバーツは、D1のストーニーブルック大学から奨学金オファーを受け取りました。

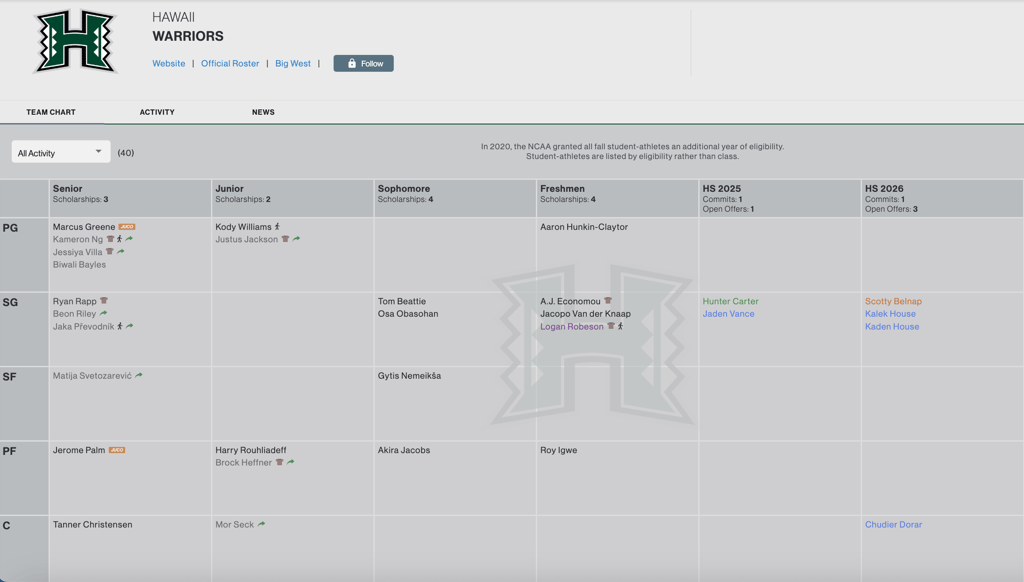

THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII'S CURRENT ROSTER AND THEIR OFFERS FOR HIGH SCHOOL PLAYERS IN THE CLASS OS 2025 AND 2026. MANY COLLEGES ARE KEEPING EYES ON THE PLAYERS FROM THEIR FRESHMAN YEAR OF HIGH SCHOOL BUT CAN OFFICIALLY MAKE AN OFFER AT THE END OF THEIR SOPHOMORE YEAR.

ハワイ大学の現在のロスターと2025年および2026年の高校生に対するオファーについて。多くの大学は、高校1年生の時点から選手に注目していますが、正式なオファーを出せるのは高校2年生終了時点からです。

SAMURAI PLAYERS GAINING EXPOSURE AND EXPERIENCE PARTICIPATING IN SUMMER AAU TOURNAMENTS IN THE US.

SAMURAI選手たちは、アメリカでの夏のAAUトーナメントに参加することで注目を集め、経験を積んでいます。